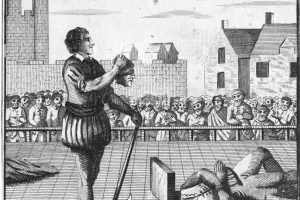

Forged iron Beheading Axe, Tribunal Inquisitionis, Venice, 1590-1640

A forged iron beheading axe, dating back to the "Venetianus Tribunal Inquisitionis," established jointly by the Venetian government and the Catholic Church, dating between the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

What makes this axe exceptionally important is the seal imprinted on the blade. It features a Patriarchal Cross and the quadripartite inscription "IVSTITIA" at the center. The phrase "Exurge Domine et Judica Causam Tuam," or "Arise, O Lord, and Judge Your Cause," frames the surrounding the seal. This phrase, taken from Psalm 74, along with the presence of the Patriarchal Cross and, above all, the distinctive iconographic construction of the seal, are the same as those found on the coat of arms of the "Sanctum Inquisitionis Officium," or "Holy Inquisition."

These fundamental details, combined with the blade's type and large size, establish with absolute certainty that it was a decapitation and mutilation axe officially used to carry out sentences resulting from the final judgments issued by the "Venetian Tribunal Inquisitionis" or "Venetian Sanctum Officium."

It can be established that it was specifically intended for the city of Venice because, during the 16th century, only two Patriarchates in Italy could adopt this type of cross: Rome and Venice. Furthermore, only the Patriarchate of the Church of Venice used this type of Venetian cross as a distinctive symbol, rather than the more common Latin cross used in Rome and all other ecclesiastical jurisdictions.

It is worth noting the presence of its original handle, which complements and enhances its already extraordinary importance.

Total length 117 cm, cut 29 cm (but originally about 35 cm).

History of the Venetian Inquisition:

The Venetian Inquisition, formally the Holy Office (Latin: Sanctum Officium), founded in the 16th century and abolished in 1797, was the court established jointly by the Venetian government and the Catholic Church to suppress heresy throughout the Republic of Venice. The Venetian Inquisition dealt not only with heresy, but also with sacrilege, apostasy, prohibited books, superstition, and witchcraft.

The court was made up of representatives of both the Venetian state and the Church, and the Holy Office had jurisdiction over the entire Republic of Venice, including overseas territories and the inquisitorial courts of other cities. It exercised significant control over Venetian society, with the aim of maintaining religious orthodoxy and repressing deviations from official doctrine. Furthermore, while maintaining a certain autonomy, the Venetian Holy Office was in constant communication with the Holy Office in Rome, from which it received directives and to which it had to submit its sentences for approval. The Venetian Inquisition was composed of members appointed by the Doge and the Patriarch (representing the Venetian state) and an inquisitor, often a Dominican, representing the Church. The seat of the Venetian Holy Office was initially the Church of San Teodoro, annexed to the Basilica of San Marco. The relationship between state and ecclesiastical power in the Venetian Inquisition has led to talk of a "mixed Inquisition," and tensions between Venetian and papal interests were frequent, especially regarding the persecution of heretics. For this reason, the Venetian Inquisition underwent changes over the centuries, with changes in its membership and its methods of functioning.

In short, the Holy Office in Venice was a unique inquisitorial tribunal, the result of a collaboration between the state and the church, with the aim of maintaining religious order and repressing any form of doctrinal dissent.

Role of the Patriarch of Venice in the Inquisition:

The Patriarch of Venice, as diocesan ordinary, had the power to try his faithful for crimes against the faith. He could act in conjunction with the Inquisitor of Venice, but was obliged to do so only in certain circumstances provided for by law.

From 1558 onward, the Patriarch or his Vicar General regularly participated as judges of faith in the sessions of the Venetian Inquisition, composed of the Apostolic Nuncio and the Inquisitor from 1541 onward, with the assistance of the Three Wise Men against Heresy from April 22, 1547.

Further information:

The Venetian Inquisition was governed primarily by the apostolic nuncio or his auditor, with the assistance of the Franciscan inquisitor (Minor Conventual) from 1541 to 1560, while the patriarchal vicar was added in 1558. From 1560, the inquisitor was a Dominican, appointed by the Congregation of the Holy Office. From then on, the judges of faith were the nuncio, the patriarch of Venice, and the Dominican inquisitor. It is uncertain when the Dominican inquisitor became the predominant judge, whether towards the end of the 16th or the 17th century.

The Venetian Inquisition functioned with the assistance of three heresy experts appointed by the Republic starting on April 22, 1547, and chosen from among the most important senators. The figure of magistrates "super inquirendis hereticis" is documented as early as the mid-13th century (Ducal Promise of Marino Morosini, June 13, 1249). The magistrate "super patarenos et usurarios" appears from 1256 (Major Council, February 14, 1256). At the end of the 13th century, the Inquisition tribunal was established in Venice.

However, in the modern era, judges were ecclesiastics, with lay people retaining the role of assistants, except in isolated trials for prohibited books in the mid-16th century, which concluded with a verdict of the Three Elders on heresy. The Council of Ten and later the Senate continued to legislate on inquisitorial activity in Venice and throughout the Republic, claiming constant state jurisdiction over the Holy Office's actions.

Two of the judges of the Venetian Inquisition, the nuncio and the inquisitor, had jurisdiction over the entire territory of the Republic, but following certain provisions of the Council of Ten, the tribunal also acted as a central body with respect to the other inquisitorial offices located in the principal cities of the Dominion: Belluno, Bergamo, Brescia, Capodistria (for Istria), Ceneda, Crema, Padua, Rovigo, Treviso, Udine, Verona, Vicenza, and Zara (for Dalmatia). Numerous trials were sent from peripheral offices to Venice in the sixteenth century, and also in the two centuries that followed. The activity of the Inquisition in Venice and the Dominion virtually ceased with the fall of the Republic in 1797, but the offices were formally abolished with the decrees of the Kingdom of Italy regarding the suppression of religious congregations between 1805 and 1810.

Bibliography:

Andrea DEL COL, L'Inquisizione romana e il potere politico nella repubblica di Venezia (1540-1560), in «Critica storica», XXVIII (1991), pp. 189-250.

Andrea DEL COL, Organizzazione, composizione e giurisdizione dei tribunali dell'Inquisizione romana nella repubblica di Venezia (1500-1550), in «Critica storica», XXV (1988), pp. 244-294.

Processi del S. Uffizio di Venezia contro ebrei e giudaizzanti (1548-1734), a cura di Pier Cesare IOLY ZORATTINI, Firenze, Olschki, 1980-1999, voll. 14.

Guida generale degli Archivi di Stato italiani, III, Roma, Ministero per i beni culturali e ambientali, Ufficio centrale per i beni archivistici, 1994., 1004-1005

Processi del S. Uffizio di Venezia contro ebrei e giudaizzanti (1548-1734), a cura di Pier Cesare IOLY ZORATTINI, Firenze, Olschki, 1980-1999, voll. 14., I, 61-63

Referenze:

Elenco delle Condanne Capitali Eseguite a Venezia - Dalle Origini della Repubblica alla Sua Caduta: