U-Boot 2524, U.D.F. 7x50 BLC (Carl Zeiss), Kriegsmarine, circa 1944

U.D.F. binoculars - U.Z.O. 7x50 produced by BLC, code name of the Carl Zeiss Jena company (at the disposal of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) in 1944, complete with rain cover tubes (only 6 complete examples known) installed and found on board the wreck of the Uboot 2524 which was recovered in 1953.

In fact, this U-boat, launched on 30 October 1944, was scuttled on 3 May 1945 in the Kattegat (Kattegat/Skagerrak was the stretch of sea where the U-boats traveled towards their combat flotillas in France or Norway), to the south-east of the island of Fehmarn in position 54.26N, 11.39E, as part of the Regenbogen operation: it remained submerged there until 1953 when it was decided to repechage it for dismantling purposes.

This operation was entrusted, in December 1953, to the SCHLICHTING-WERFT company located in Lübeck-Travemünde. In fact, applied to the body of the binoculars there is a metal label, with an inviolate seal of the SCHLICHTING-WERFT Lübeck-Travemünde dated '53, within which there is a tag on which some information from the Archive, Registry, Wreck etc etc is shown.

Furthermore, on one of the 2 covers of the rainproof tubes, each of which bears the same serial or assignment number, there is a summary card from SCHLICHTING-WERFT Lübeck-Travemünde, on which there is the same archive number as the card placed on the body of the binoculars.

The binoculars, which spent approximately 8 years in the depths of the sea, are in good condition: the optical part is completely opaque and abraded by the sand/sea and the paint is not present. The body of the binoculars also did not suffer excessive corrosion from sea water as it was originally protected by a thick layer of paint which preserved it for a longer time.

Historical find of exceptional importance as, of the 30 German U-boats sunk in the Kattegat area, only 6 examples have been recovered since the end of the war and these are the U-3503 in 1946, U-2338 in 1952, U-2425 in 1953, U-2365 in 1956, U-843 in 1958 and U-534 in 1993.

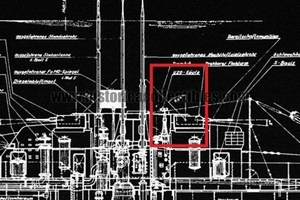

U-2524 (from http://www.ubootarchiv.de)

Typ:XXI

Bauauftrag: 06.11.1943

Bauwerft: Blohm & Voss, Hamburg

Baunummer: 2524

Serie: U2501 - U2564

Kiellegung: 06.09.1944

Stapellauf: 30.10.1944

Indienststellung: 16.01.1945

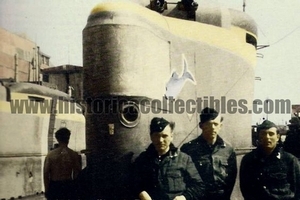

Kommandant: Ernst von Witzendorff

Feldpostnummer: M - 49 299

Die Kommandanten

16.01.1945 - 00.04.1945 Kapitänleutnant Ernst von Witzendorff

00.04.1945 - 00.04.1945 Oberleutnant zur SeeGünter Dobenecker

00.04.1945 - 03.05.1945 Kapitänleutnant Ernst von Witzendorff

Flottillen

16.01.1945 - 03.05.1945 Ausbildungsboot31. U-Flottille

Erprobung und Ausbildung

16.01.1945 - 03.05.1945 Erprobungen und Ausbildung bei den einzelnen Kommandos (UAK, TEK, AGRU-Front usw.) und Ausbildungs-flottillen.

Die Unternehmungen

00.02.1945 - Danzig→ → → → → → → → →00.02.1945 - Gotenhafen

00.02.1945 - Gotenhafen→ → → → → → → → →00.02.1945 - Warnemünde

U2524, unter Kapitänleutnant Ernst von Witzendorff, lief im Februar 1945 von Danzig aus. Das Boot verlegte, über Gotenhafen, nach Warnemünde. An Bord befanden sich 25 - 30 Flüchtlinge aus dem Osten.

Die Verlustursache

Boot: U2524

Datum: 03.05.1945

Letzter Kommandant: Ernst von Witzendorff

Ort: Ostsee

Position: 54°26,26' Nord - 11°32,29' Ost

Planquadrat: AO 7824

Verlust durch: Raketen und Bordwaffen

Tote: 1

History:

On May 3, 1945, in the Baltic Sea east of Fehmarn, U2524 was damaged by rocket and on-board weapon fire from Bristol Beaufighters of the British Squadrons 236 and 254 and then sunk by the crew themselves.

30 "Beaufighters" from the British Squadrons 236 and 254, escorted by North American P-51 Mustangs from the British Squadrons 65 and 118 and Hawker Typhoons from the Strike Wings of the British 16th Group of the 2nd Tactical Air Force with Squadron's 175, 184 and 245 , discovered the German target ship BOLKOBURG, on whose starboard side the boats U2524, U2549 and U3032 had moored, and U3030, which was still waiting some distance away. During the first attack on the BOLKOBURG, it was hit by, among other things, a rocket bomb, an unexploded bomb, which penetrated the ship's superstructure and hit the forecastle of U2524. The pressure hull sustained minor damage on the starboard side of the bow compartment. The part of the crew that was already on the BOLKOBURG was immediately ordered back on board U2524.

Because of the enemy aircraft constantly approaching, the commander ordered the ship to cast off and dive near the ship. Water entered the boat through a small crack in the pressure hull, but this did not pose a major danger given the shallow water depth of 24 meters.

The scuttling was prepared while lying on the ground and contact was made with the torpedo boat LÖWE using UT (underwater telephone). After dusk the surface surfaced and both boats quickly moved alongside. After the crew had been transferred to the torpedo boat, only the chief engineer, Oberleutnant (Ing.) Werner Braun and the central mate Josef Ritter remained on board to initiate the scuttling. From the torpedo boat LÖWE, the crew watched as their boat sank slowly and steadily.

The boat was almost under water when the central mate appeared excitedly on the bridge. He was picked up by an inflatable boat that was kept ready, then U2524 sank very quickly into the water with the chief engineer Werner Braun on board. As the crew later learned from the central mate, Werner Braun voluntarily stayed on board the sinking boat. The torpedo boat LÖWE took the crew to Flensburg-Mürwik, where they saw the end of the war. The wreck of U2524 was lifted in 1953 and taken to the scrap landing site in Travemünde. During the rescue work, the remains of Werner Braun, then 28 years old, were found and buried in Lübeck.

Historie Schlichting-Werft (from www.schlichting-werft.de):

Construction number 1, entered on October 10, 1898 as the first order in the business book of the Johannes Schlichting yacht and boat yard, was a fish box.

Not a small box as you might know it today. In order to keep fish fresh for a long time after they were caught, they were locked in large wooden boxes that were firmly moored in the harbor basin. The fish swam there until a buyer was found.

The workshop in which Johannes Schlichting and his brother Heinrich completed the first orders was no larger than 70 square meters. It first had to be built in the newly purchased house at Marktstrasse 19, directly opposite the Travemünde Church.

The properties in what is now the annual market street were waterfront properties until the 1930s. The dredged sand had not yet been piled up and the sick bay, as part of the Trave, went up to the garden fence of the new shipyard.

A small slipway led into the shallow water and brought the first orders ashore. Mainly repairs to fishing boats from Schlutup and Travemünde, but also the first new buildings such as dinghies, sand barges and, at the beginning of 1900, the first two sailing yachts were launched behind the market square.

In addition to Johannes Schlichting and his brother Heinrich, the workforce also included wheelwright Jean Kruse and a first apprentice. After a short time, the owners of smaller and larger yachts from the Lübeck Yacht Club discovered the qualities of the Schlichting shipyard, but their often deep ships could not reach the shipyard's winter storage across the shallow water.

In a letter, the board of the Lübeck Yacht Club wrote to the Lübeck city administrators and asked for a new property for Johannes Schlichting and his shipyard. This was quickly found, exactly opposite on the Priwall next to the ferry. New land was created there by adding sand and the shipyard moved to Priwall in 1905.

But it wasn't just the Lübeck sailors who were looking for a suitable shipyard and a safe storage facility for their small and large yachts in the winter.

Yachts from Kiel and Hamburg came to Travemünde more and more often, and not just for Travemünde Week. Johannes Schlichting had to adapt his shipyard to these new needs and constantly expand it.

A corrugated iron shack with a fire and a drill for blacksmithing and locksmith work was built and the first power machine with 10 hp powered a band saw and a thickness planer in the carpentry shop.

A dynamo machine provided electric light and replaced the many petroleum lamps on the shipyard premises.

The construction of workboats, lifeboats, small yachts and dinghies ensured a secure income for more and more Travemünde craftsmen and the workforce at the Schlichting shipyard developed an excellent reputation far beyond the city limits.

The “Nationale Jolle” named “Ahasaver”, designed by Johannes Schlichting himself, sailed to victory in 23 regattas in just one season and underlined the quality of the yachts built at the shipyard.

This was followed by the First World War and the first serious crisis for the shipyard. Johannes Schlichting and almost the entire workforce were drafted into military service at the front. Only his brother Heinrich, along with a few boat builders, were allowed to stay at the shipyard to work.

But in 1915, Johannes Schlichting returned decorated with an Iron Cross, on leave from the war to build boats for the Imperial Navy. Due to the great need for smaller vessels from the war-strengthened navy, additional boat builders had to be hired.

But the artificial war boom was followed by economic collapse after the capitulation in the German Reich and difficult times began for shipbuilding and the Schlichting shipyard.

The rescue after the First World War brought large orders for the construction of lifeboats in the truest sense of the word. In the 1920s, a good 225 of them were built at the shipyard. Including, for the first time, motor lifeboats for large shipping companies with a capacity of 50 people.

At first sluggish during the times of inflation, but later increasingly stronger, yacht building on the Priwall also picked up again and led the Schlichting shipyard to new prosperity.

Based on the experience of the previous difficult years, Johannes Schlichting made his shipyard more economically crisis-proof and built a new winter storage hall with a length of 65 meters and a width of 34 meters and was now finally able to offer his many yacht customers a covered winter storage facility.

The approximately 100 meter long Hall F followed at the end of the 1920s. Yachts up to 26 meters long and 80 tons in weight could be accommodated via the two slipways and a connected rail system. The yachts built at the Schlichting shipyard were of high quality craftsmanship and were considered fast and seaworthy. Ship names such as “Susewind”, a participant in an Atlantic race in 1936, “Kapitän Harm”, a cruiser yacht measuring 16.75 meters and 180 square meters of sail area, or “Thalata”, which belonged to the then very well-known sailor Adolf Kirsten, carried the name Schlichting further into the history World.

Owners from Lake Constance to Flensburg came to Travemünde to have their ships built by Johannes Schlichting. The largest yacht of this time was the “Ingorata” with a length of more than 18 meters and a sail area of 185 square meters. She is still sailing off Warnemünde today, freshly renovated.

The global economic crisis followed in the early 1930s. It left neither Travemünde nor the Schlichting shipyard without a trace. With the company since 1924, Rudolf Schlichting works hand in hand with his father Johannes to keep the business running despite the economic downturn. The workforce had meanwhile fallen to 40 employees.

Once again it was orders for lifeboats that saved the shipyard just in time and saved it from the worst. The navy, which grew rapidly as a result of National Socialism, brought further large orders. The air force and the testing site on the Priwall needed safety boats, the navy needed mine clearing and speed boats, and the shipyard's capacity needed to grow quickly for the war machine.

The shipyard area was almost doubled in 1936 and 1937 to 28,500 square meters, of which 13,000 square meters were covered with halls. From 1943 to 1945 the shipyard reached the peak of its performance. A speedboat left the shipyard every 14 days, a total of 50 units. Built entirely of wood, with a length of 35 meters and three engines with 3,000 hp each, the boats required enormous logistics at the shipyard.

Rudolf Schlichting, who was given management of the shipyard by his father in 1943, himself selected the wood from the forests to build the ships, while Johannes Schlichting supervised the work at the shipyard. Many shipyard employees were drafted to the front and their absence was filled with foreign workers from all over Europe. At times almost 1,000 people worked at the Schlichting shipyard.

In May 1945 the Third Reich collapsed in Travemünde and with it came the English as occupiers. As early as June 1945, Rudolf Schlichting received permission to hire 50 men again to initially clean up the company and remove any war work that had been left behind. Once again it was the construction of lifeboats that gave hope for new work in the severe crisis, and it was the occupiers themselves who gave the order for this.

After many restless years of work at the shipyard, Johannes Schlichting died in 1946 at the age of 75 and, as fate would have it, his son Rudolf Schlichting also died of illness in September of the same year. Without economic prospects, the shipyard and family were left with practically nothing. The lack of shipbuilding orders was partially bridged with work as a body shop, but was closed after a fire in a hall.

After fifty years of wooden boat building, the connection to steel ship building had not been initiated in time, which made the order situation even more difficult. Of all things, the first small steel freighter “Antonia” built at the Schlichting shipyard led to major financial difficulties for the shipyard because the new shipowner was unable to pay. Thekla Schlichting and her sons Peter and Klaus had to register for a settlement on September 25, 1953.

The process dragged on until 1954, when the Hamburg entrepreneur and shipbuilding engineer Alnwick Harmstorf bought the Schlichting shipyard. Not only did the era of the Schlichtings at the Schlichting shipyard come to an end, only Peter Schlichting worked at the shipyard as head of the marine department until the end of 1986, the shipyard also changed its face into one of the most modern shipyards in Europe.

Their area grew to almost 140,000 square meters. Bulk carriers, general cargo ships, research ships, special ships and naval ships were now industrially manufactured to the highest standards. The launches from the 180 meter long heel on which the freighters of up to 30,000 tdw were built were not only an event for Travemünder. Shipbuilding at the Schlichting shipyard was just as much a part of Travemünde's cityscape as the church and later the Maritim.

Literaturverweise:

Rainer Busch/Hans J. RöllDer U-Boot-Krieg 1939 - 1945 - Die deutschen U-Boot-Kommandanten (1996 - Mittler Verlag - ISBN-978-3813204902. - Seite 51, 258).

Rainer Busch/Hans J. RöllDer U-Boot-Krieg 1939 - 1945 - Der U-Boot-Bau auf deutschen Werften 1935 - 1945 (1997 - Mittler Verlag - ISBN-978-3813205121 - Seite 175, 225).

Rainer Busch/Hans J. RöllDer U-Boot-Krieg 1939 - 1945 - Die deutschen U-Boot-Verluste September 1939 - Mai 1945 (2008 - Mittler Verlag - ISBN-978-3813205145 - Seite 348, 349, 350, 357).

Herbert RitschelKurzfassung Kriegstagebücher Deutscher U-Boote 1939 - 1945 - KTB U 1101 - U 4718 (2012 - Eigenverlag ohne ISBN - Seite 134).

Eckard Wetzel: U2540 Das U-Boot beim Deutschen Schiffahrtsmnuseum in Bremerhaven, Karl Müller Verlag, Erlangen 1996, ISBN 3 86070 556 3, (Seite 240 bis Seite 244).

Georg Högel: Embleme, Wappen, Malings deutscher U-Boote 1939–1945. 5. Auflage. Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7822-1002-7, Seite 183.

Rainer Busch, Hans-Joachim Röll: Der U-Boot-Krieg 1939–1945. Band 1: Die deutschen U-Boot-Kommandanten. E. S. Mittler und Sohn, Hamburg u. a. 1996, ISBN 3-8132-0490-1, Seite 258.

Axel Niestlé: "German U-Boat Losses of World War II. Details of Destruction", Frontline Books, London 2014, ISBN 978-1-84832-210-3, Seite 159.

Rainer Busch, Hans-Joachim Röll: Der U-Boot-Krieg 1939–1945. Band 2: Der U-Boot-Bau auf deutschen Werften. E. S. Mittler und Sohn, Hamburg u. a. 1997, ISBN 3-8132-0512-6. Seite 228.