Depth Gauge of the Royal Submarine "Ammiraglio Cagni", Italian Royal Navy, circa 1939

Depth gauge or depth indicator in "meters of sea water column" installed aboard, starting in 1939, one of the most important and legendary ocean-going submarines of the Royal Italian Navy, the "Admiral Cagni."

In fact, this "Depth Gauge," made by S.I.M. (name of Società Italiana Manometri - Milan) for the Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico-Cantieri di Monfalcone shipyards, is accompanied by an official military paper label, Mod. DP/30XX "unusable material without recovery," printed and sealed with lead. The label contains references, numerical data, and inscriptions signed by the Officer in Charge of the Logistics Office of the Taranto Naval Arsenal. He confirms that it was an integral part of the onboard instrumentation of the Royal Submarine "Ammiraglio Cagni" and that this instrument must be sent for scrapping because it was deemed obsolete.

The Royal Submarine "Ammiraglio Cagni" was sent for scrapping in 1948, and in all likelihood, this "Depth Indicator" was stored in some military warehouse and forgotten until, on October 15, 1959, it was decided to send it for scrapping/destruction.

This "Depth Indicator" or Depth Gauge features a graduated scale measuring from "0" to "120" meters of seawater, divided meter by meter. It also features a precision oil-bubble "clinometer" mounted on its dial (with a 0° to 20° scale on port and starboard, divided degree by degree). This served to indicate the degrees of inclination at which the submarine submerged or surfaced. It was also useful for controlling, during surface navigation in rough seas, the roll of the hull's longitudinal axis and avoiding situations of instability that could have caused a rare but potentially catastrophic capsize.

Furthermore, the brass structure bears an acceptance stamp from the Royal Navy, consisting of an "anchor" with a "fascio littorio" and a "crown of Savoy."

The depth gauge has a diameter of 43.5 cm, a thickness of 8 cm, and weighs approximately 10 kg.

It is one of the very few surviving wartime depth gauges. The turret of the Royal Submarine "Ammiraglio Cagni" was preserved and is still on display as a monument at the Taranto Arsenal.

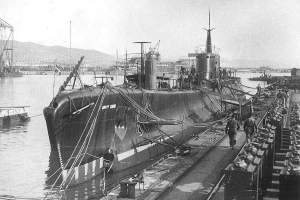

History of the Royal Submarine Admiral Cagni:

Commissioned on April 1, 1941, in Monfalcone, command was supposed to be assigned to Lieutenant Commander Romeo Romei, who, along with a large portion of the Pier Capponi's crew, was actually killed the day before in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

After completing training in October 1941, due to its large size, it was assigned to transport supplies to Libya.

On October 14 (with Lieutenant Commander Carlo Liannazza as commander), it sailed from Taranto to Bardia for its first mission, transporting 140 tons of ammunition. It completed the task and returned to Taranto on the 22nd, also escaping shelling and depth charge attacks.

On November 18, it completed a second such mission.

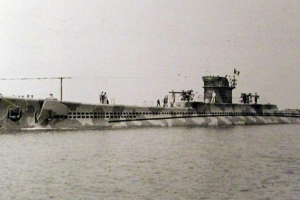

In total, she carried out five offensive-exploratory missions in the Mediterranean, five transport missions (delivering a total of 419.5 tons of fuel, 328.5 tons of ammunition, and 147.5 tons of supplies), and 16 transfer missions, for a total of 11,638 miles of surface navigation and 570 miles submerged.

After a series of refits to adapt to ocean conditions, she was sent to operate in the Atlantic (and, if possible, an offensive foray into the Indian Ocean was also considered).

On October 6, 1942, the Cagni left La Maddalena under the command of Carlo Liannazza (who had since been promoted to frigate captain); six days later, she passed the Strait of Gibraltar. The submarine was scheduled to operate in the South Atlantic off the coast of Africa (in addition to attempting the aforementioned offensive foray into the Indian Ocean). On November 3, the Cagni torpedoed and sank the British armed motor vessel Dagomba (3,485 GRT), belonging to convoy "TS. 23," off the coast of Freetown; during the next 26 days of navigation, there were no sightings. Only on November 29, just after arriving near Cape Town, did the submarine encounter another merchant vessel, the Greek steamer Argo (1,995 GRT), which was sunk near the Cape of Good Hope with four torpedoes (two of which hit).

Remaining in the Cape Town area until December 8, the Cagni headed further north (forgoing entry into the Indian Ocean because a planned refueling mission had not been carried out) and on January 3, 1943, she rendezvoused with the submarine Tazzoli, which she was supposed to refuel with eight torpedoes (the Tazzoli had three, the Cagni 29), an operation that could not be carried out due to rough seas. On the 13th, the Cagni took on 45 tons of fuel oil from the German submarine U. 459 and was then sent to operate in South American waters, first off Cape St. Rocco and then off the island of St. Paul (the Tazzoli was supposed to have sailed to those waters, but since it had run out of torpedoes, it was decided to send the Cagni to replace it); on January 22, she set out on her return voyage without encountering any other ships. On February 15, she was bombed and strafed by a Short Sunderland in the Bay of Biscay, leaving one casualty on board (Sergeant Michelangelo Canistrari) and one wounded. However, she managed to repel and even shoot the vessel, reaching Bordeaux (home of the Betasom Atlantic base) five days later.

With 136 days at sea, the Cagni's mission was the longest ever carried out by an Italian submarine.

Later modified to carry supplies, on June 29, 1943, the Cagni set sail under the command of Lieutenant Commander Giuseppe Roselli Lorenzini for a "hybrid" mission: an offensive mission across the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, and the China Sea, arriving in Singapore and returning with a cargo of rubber and tin.

After crossing the submerged Bay of Biscay, on July 17, the submarine attacked a British armed merchantman of approximately 5,000-6,000 GRT with three torpedoes. The guns missed their target, and the ship's reaction forced the Cagni to turn away, although the Cagni was deemed to have damaged the target. Four days later, off the coast of Freetown, another unsuccessful two-torpedo launch occurred against an auxiliary cruiser armed with four medium-caliber guns and six quadruple machine guns.

On July 25, the Cagni encountered a convoy on the Bahia-Freetown route, approximately 500 miles from the latter city. It consisted of a large floating dock, six light ships, and the large British auxiliary cruiser Asturias, converted from a 22,048-ton passenger ship. The Cagni fired two 6,500-meter torpedoes at the Asturias, submerging immediately afterward. The large ship was hit and immobilized (four casualties occurred), but, although many compartments were flooded, she managed to reach the port of Freetown—towed by the powerful Dutch tug Zwarte Zee and assisted by a corvette. Run aground, she was declared lost (in reality, in February 1945, she was repaired as best she could, towed to Gibraltar and rebuilt, returning to service in mid-1946).

Having crossed the equator on July 28, on August 22, Betasom command ordered the submarine to head directly for Singapore (originally planned to lie in wait off Cape Town), and six days later, the Cagni entered the Indian Ocean.

On the night of September 8–9, 1943, when the armistice was announced, the submarine was 720 miles southeast of Mauritius (and about 1,800 miles from Singapore) and reversed course. However, it proceeded very slowly while awaiting further information to clarify the situation. On September 12, Commander Roselli Lorenzini—despite the invitation from Captain Enzo Grossi, commander of Betasom, to continue the war alongside the Germans—decided to follow the order and surrender to the Allies; the Cagni arrived in Durban on September 20, 1943, receiving the honors of war.

On November 8, 1943, the submarine departed for homeland and, following the route Durban-Mombasa-Aden-Port Said-Haifa-Taranto, the Cagni returned to its Italian base on January 2, 1944.

The submarine was subsequently deployed in Allied anti-submarine exercises, based in Palermo, under Lieutenant Commander Rino Erler from April 26, 1944, to February 11, 1945.

Disarmed at the end of the war and decommissioned on February 1, 1948, it was sent for scrapping; the turret was preserved and is still displayed as a monument at the Taranto Arsenal.